Workhorse Blues is one of a number of songs on Workhorse that revolves around life choices. I guess when you get to this stage in life you start looking at the paths taken and not taken, sometimes with relief, sometimes with regret.

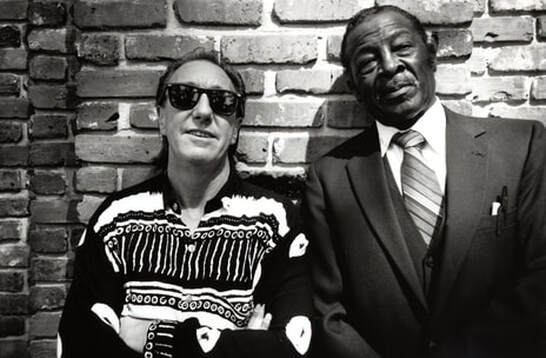

Midge Marsden & Willie J Foster

Midge Marsden & Willie J Foster There were many inspirations behind the lyric. Tom Waits is in there somewhere, but then he usually is... But the person perhaps most on my mind was a bluesman from America who traveled to New Zealand and toured with Midge Marsden in the nineties. His name was“Mississippi” Willie Foster. I'd guess he was in his seventies then.

Actually, that was only his name in New Zealand. We were lucky enough to play support for him a couple of times and I also interviewed him for the local paper. As he pointed out, it's not much use being called “Mississippi” Willie Foster if you're in Mississippi. And Willie hadn't left Mississippi since the '60s. Back there he was called “Little” Willie Foster.

Willie was a sweet and dignified man. New Zealand was a country he didn't really know before Midge met him, and everything seemed like some fever dream, a truly bizarre experience, suddenly being a star in a far-off country and having crowds of mainly young - mainly white - people fete him wherever he went. If you've ever been to Mississippi you'll realise quite how important the word “white” is in that sentence, and how strange it was for Willie.

Willie told me he was born “like a rabbit” between the rows of a cotton field (in 1921). His mother went into labour while picking cotton on the plantation where she sharecropped. He told me about seeing Muddy Waters perform at the Dunleith plantation before the war, and he also remembered a visit by John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson. That's the first Sonny Boy, not the more famous Chicago harp player who Willie didn't like at all – reckoned he swore and drank too much...

Willie told me about his own days sharecropping. He'd done that until he signed up for the army and was posted to England during World War 2. Sharecropping was hard. He said to me: “We used to work out in those fields from cin till cain't.”

“Say what?” I asked. That was a new one to me.

“Cin till cain't? That's from when you cin see till when you cain't see” said Willie.

I saved that for 25 years to put in a song.

Actually, that was only his name in New Zealand. We were lucky enough to play support for him a couple of times and I also interviewed him for the local paper. As he pointed out, it's not much use being called “Mississippi” Willie Foster if you're in Mississippi. And Willie hadn't left Mississippi since the '60s. Back there he was called “Little” Willie Foster.

Willie was a sweet and dignified man. New Zealand was a country he didn't really know before Midge met him, and everything seemed like some fever dream, a truly bizarre experience, suddenly being a star in a far-off country and having crowds of mainly young - mainly white - people fete him wherever he went. If you've ever been to Mississippi you'll realise quite how important the word “white” is in that sentence, and how strange it was for Willie.

Willie told me he was born “like a rabbit” between the rows of a cotton field (in 1921). His mother went into labour while picking cotton on the plantation where she sharecropped. He told me about seeing Muddy Waters perform at the Dunleith plantation before the war, and he also remembered a visit by John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson. That's the first Sonny Boy, not the more famous Chicago harp player who Willie didn't like at all – reckoned he swore and drank too much...

Willie told me about his own days sharecropping. He'd done that until he signed up for the army and was posted to England during World War 2. Sharecropping was hard. He said to me: “We used to work out in those fields from cin till cain't.”

“Say what?” I asked. That was a new one to me.

“Cin till cain't? That's from when you cin see till when you cain't see” said Willie.

I saved that for 25 years to put in a song.

Please note: the description below this video on YouTube is referring to a different Willie Foster

RSS Feed

RSS Feed